In November, Prison Law Office joined the firm of Keker, Van Nest & Peters, the A.C.L.U., and the California Collaborative for Immigrant Justice in filing a class-action lawsuit against ICE and the Department of Homeland Security on behalf of those detained at California City. As noted in the filing, detainees refer to C.C.D.F. as a “torture chamber” and “hell on Earth.” In fact, Borden says, the conditions at the facility are so terrible that detainees are resigning themselves to self-deportation, instead of pursuing asylum and other immigration cases, and that “people are also trying to take their own lives.”

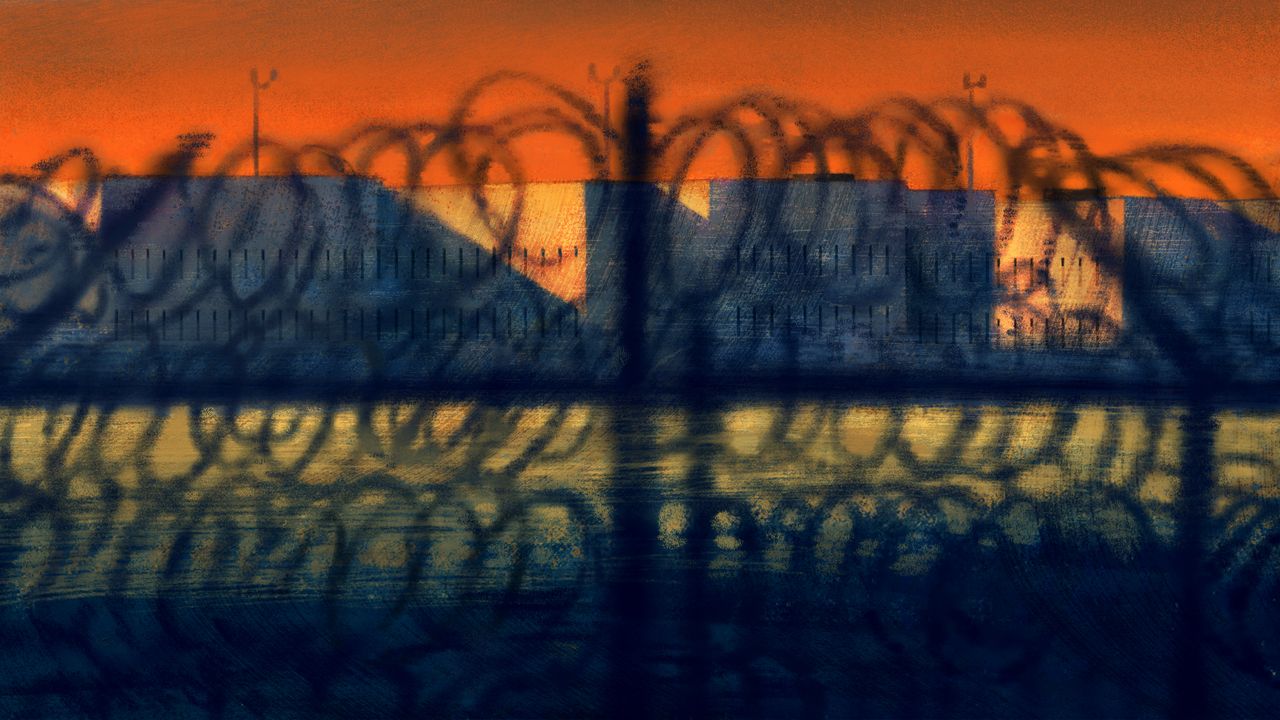

In April, 2025, as deportations ramped up nationwide, the for-profit prison company CoreCivic repurposed a decommissioned prison in California City into an immigration detention center after signing a contract with ICE. The company already owned the prison, which had sat unused since 2023, so the contract, which is worth an estimated a hundred and thirty million dollars annually, was a valuable source of revenue for CoreCivic. Additionally, the CoreCivic property has helped address ICE’s growing need for detention space in a state where the agency has turbocharged its immigration-enforcement activities. If fully occupied, C.C.D.F. will be the largest detention center on the West Coast—and one of its most remote.

C.C.D.F. is situated two hours north of Los Angeles, deep in the Mojave Desert, and about sixty miles from the edge of Death Valley National Park. Temperatures can be below freezing in the winter, and well over a hundred degrees in the summer. “It’s hard for attorneys to get out there,” Mario Valenzuela, a lawyer who represents multiple clients at C.C.D.F, told me. It is a three-hour round trip from Valenzuela’s office in Bakersfield out to California City, and the detention center is so desolate that he often can’t find cell service. He told me, “There’s nothing around, just barren desert, then all of a sudden you come across this facility.”

The closest town to C.C.D.F. is California City, about five miles away, where about a quarter of residents live below the poverty line, and roughly eighteen per cent are unemployed. As of 2024, CoreCivic is one of the town’s largest employers. But, despite signing a contract with ICE, ongoing litigation alleges that the company has not secured a business license or the proper conditional-use permit for the facility with the municipal government of California City. Since it opened, C.C.D.F. has allegedly been operating in direct violation of A.B. 103, a state law that requires a hundred-and-eighty-day waiting period and two public hearings before a private corporation may repurpose a facility as an immigration detention center. An active lawsuit is currently deciding these claims, but, even if the courts side with CoreCivic, the company seems to have acted in a legal gray zone when opening C.C.D.F.

On August 27th, CoreCivic began receiving detainees at C.C.D.F. In September, a federally authorized monitor visit by Disability Rights California raised “serious concerns” about the facility’s significant disrepair, caused by the period it sat vacant and the subsequent “rush to open.” That month, five hundred migrants were believed to have been transferred to C.C.D.F. In November, Prison Law Office estimated that eight hundred detainees were being held at the facility, and by mid-January the count was fourteen hundred. C.C.D.F. is projected to reach its full capacity of two thousand five hundred and sixty people in the first quarter of 2026.

“Any claims there are inhumane conditions at the California City Correctional Facility are FALSE,” the D.H.S. assistant secretary for public affairs, Tricia McLaughlin, said in an e-mail, adding that “ICE is regularly audited and inspected by external agencies” to insure its facilities comply with “national detention standards.” With regard to medical treatment, McLaughlin said that the agency provides “comprehensive medical care.” A representative for CoreCivic added that the company has “submitted all required information for a business license and [continues] to maintain open lines of communication with city officials.”

Still, as detainee numbers have surged, staffing and basic infrastructure have clearly not kept up. In a letter sent to D.H.S. last month, California’s attorney general, Rob Bonta, warned that “the facility does not have enough medical doctors for its detainee population size,” and the staff it does have “appear to be inexperienced and lack basic understanding of civil detention management principles.” On January 20th, Senators Alex Padilla and Adam Schiff toured the facility and spoke with the warden as part of an oversight visit. “Far and away, the biggest concerns were about lack of medical attention,” Senator Padilla told me by phone after his visit. He compared the facility’s conditions to what he saw during a tour of migrant detention facilities at Guantanamo Bay last year, explaining that it can take “weeks or months” for a detainee to receive care, “even for matters that, in my mind, seem pretty urgent.”